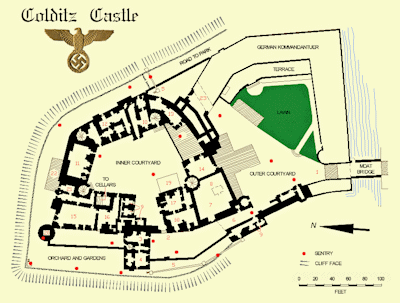

During World War II, the Germans remodeled a 400-year-old building called Colditz Castle (Schloss Colditz), a Renaissance castle located in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden, and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony in Germany. It overlooked the Mulde River and had 7-foot thick outside walls. The interior of the 6-story structure contained a maze of concealed staircases, hidden passageways, and hundreds of rooms.

When they completed the work to turn the building into a prison, the Germans renamed it Oflag IV C (Sonderlager IV C) and claimed that escape would be impossible. It became the holding place for highly important prisoners and those that habitually tried to escape from other prisons.

On November 7, 1940, six British officers who had tried to escape from another prison camp arrived, including Rupert Barry. My towering and strong fictional character, Tom, is based on stalwart and faithful Rupert.

By Christmas, Colditz Castle held 200 prisoners—the maximum it could contain. By February 1941, another 200 French prisoners had arrived, doubling the maximum occupancy rate. By July, the Nazis held 500 POWs there.

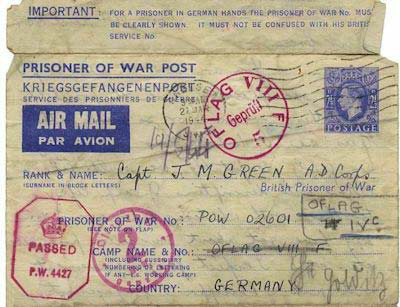

Two of the British officers, Captain P. R. Reid and Captain Rupert Barry, worked together to create a code that Barry then wrote in a letter to his wife, Dodo, upon whom the fictional Dotty, code-named Charity, is based. The real-life heroine, Dodo Barry, was a highly intelligent woman who could solve the complicated Times of London crossword puzzle in mere minutes. Captain Rupert Barry doted upon his beloved wife and, what’s more, he deeply appreciated and respected her keen mind. He felt more than confident in his wife’s abilities to crack the code they devised.

The mailing address being written on an angle trailing up toward the stamp in the fictional story of Charity is a fiction based on numerous such factual occurrences throughout history. Soldiers during the American War Between the States would do this, hiding secret love messages beneath the postage stamps. Many spies used the same method during the First World War. During the Second World War, spies on all sides would hide microdots beneath postage stamps. The method of hiding keys and codes “under the rug” of a postage stamp became so popular that a key to a cipher code was even hidden beneath a postage stamp in a famous Agatha Christie story.

In real life, upon receiving the letter, Dodo at first thought that conditions as a German POW had broken her dear husband’s mind. He wrote about relatives they didn’t have and referred to places they’d never visited. Then she realized that he’d written the letter in code, and she spent the day deciphering the letter using nothing but her very own wits.

Decoded, it read:

Go to the War Office, ask them to send forged Swedish diplomatic papers for Reid, Howe, Allan, Lockwood, Elliott, Wardle, Milne, and self.

The next morning, Dodo went to the War Office. The officer at the desk would not let her into the building. While she stood in front of the clerk’s desk arguing with him, another officer walked by, and she pleaded with him to help her. As if by providence, the officer happened to be assigned to military intelligence, a military branch with ties to MI-9.

The officer, whose name is lost to history, realized Dodo was onto something. He started working with her and had her write back to her husband and tell him, without code, that his elderly “Aunt Christine” was deeply saddened by her nephew’s capture and would write him shortly.

Under that guise, and using the same code the prisoners had created, and Dodo had deciphered, the War Office sent him a coded letter that said:

The War Office considered the use of Swedish diplomatic papers to be too dangerous.

Angry, disappointed, and frustrated with the news, instead of writing “Aunt Christine” back, Barry wrote Dodo back. Once she received his second encoded letter, she took it back to her contact at the War Office.

The deciphered message read:

We will consider the danger and not the War Office. Would you please expedite the request?

The War Office never sent the papers. However, these first “Dodo” letters had opened up a line of communication between the War Office, MI-9, and the POWs being held at Colditz Castle.

Of absolute primary importance, they needed to establish a better code.

To anyone who spoke English, the simply encoded letters would have read as a little bit odd or disjointed. The Nazi censors often only had a rudimentary grasp of the English language, so they were able to slip by unnoticed. However, four letters in this rudimentary code was pushing their luck. Eventually, they felt the Nazis would catch on and have insight into their plans.

Under the direction of her intelligence officer, Dodo wrote a letter to Rupert explaining that an International Red Cross package would arrive with further instructions. Along with some clothing, one package contained six handkerchiefs with different colored borders. Coded instructions in Dodo’s letter directed Barry to place the green bordered handkerchief in hot water and stir for several minutes. Soon, a more elaborate code appeared in hidden ink on the handkerchief. Barry memorized the code then destroyed the material. Over time, he shared the code with his fellow prisoners, who also committed it to memory.

With well-coded letters and hidden supplies contained in Red Cross packages, the MI-9 office (escape and evasion service) supplied the prisoners in Colditz with money, identification documents, radios, tools, train schedules, border crossing policies and routines, clothing, and even weapons.

The war effort was greatly aided by critical intelligence sent home from the prisoners. One such prisoner, a skilled dentist, was often called upon to treat German soldiers and officers as well as his fellow prisoners. He sent letters back home to Scotland and the ones that began “Dear Dad” often contained crucial information pertaining to troop movements inside Germany.

With the aid of the secreted supplies and intelligence that MI-9 could provide via this now secure communication channel, one hundred and thirty prisoners escaped from Colditz Castle—either successfully or unsuccessfully—over a five-year period.

Of those one hundred and thirty escaped prisoners, thirty-two of them successfully escaped. In all, twelve Frenchmen, eleven Britons, seven Dutch, and one Polish prisoner of war made it all the way home, a feat that came to be known as a Home Run. This number of prisoners of war escaping and making it all the way back home is unequaled in modern warfare. Among these successful escapees was Captain P. R. Reid, who had helped Rupert Barry pen that very first letter to his wife, Dodo.

Because of Dodo, also the name of a now-extinct bird, the Colditz Castle escapees came to be known as the “Birdmen of Colditz,” and their escapes and attempted escapes have been the subject of many books, films, and even a BBC television series. Very few photographs of Dodo or her husband survive today.

Read about Dorothy Ewing who was inspired by Dodo Barry in Charity’s Code, part 3 of the Virtues and Valor series.

Charity’s Code

DORTHY EWING works on the home-front, receiving and sending messages to her team in France and coordinating a secret mission. She receives and sends messages to her team in France and coordinates a secret mission with her husband via coded letters. She intercepts the transmission from TEMPERANCE alerting to her blown cover. The clock is ticking in a race to save Temperance's life.

Save $0.50 by clicking the button below to order this book directly from Hallee. Otherwise, click the "order now" button to buy it from your favorite retailer.