WHILE the story of the special team of operators I named The Virtues is entirely fictional, set in a fictional town, and comprised of fictional characters who form a fictional military division, every single one of my fictional heavenly heroines was inspired by a real World War II heroine and the story was inspired by real events.

WHILE the story of the special team of operators I named The Virtues is entirely fictional, set in a fictional town, and comprised of fictional characters who form a fictional military division, every single one of my fictional heavenly heroines was inspired by a real World War II heroine and the story was inspired by real events.

Today, Charity’s Code IS FREE. Yes! FREE. You can get it in ebook form at this link.

Here are the amazing stories that inspired the writing of Charity’s Code, Part 3 of the Virtues and Valor Serialized Story.

WHILE the story of the special team of operators I named The Virtues is entirely fictional, set in a fictional town, and comprised of fictional characters who form a fictional military division, every single one of these fictional heavenly heroines was inspired by a real World War II heroine and their story was inspired by real events.

While every effort has been made to remain true to actual history, two of the real events of significance that are fictionalized in the story of Charity are the Blitzkrieg, also sometimes referred to as the Battle of Britain, and the British Ministry of Health Evacuation Scheme, which was the program to relocate the children of England to the countryside for the duration.

On the first of July in 1940, the freshly bloodied Luftwaffe capitalized on successful bombing raids against Poland and Holland, dropping the first bombs on England. The bombing would escalate into the Blitzkrieg, and between 7 September 1940 and 21 May 1941 there were almost daily (or nightly) major aerial raids on 16 British cities. The attacks resulted in more than 100 tonnes of high explosives being dropped on mostly civilian targets in England.

The Luftwaffe bombed Great Britain for 57 consecutive nights starting on 7 September 1940. Destroying or damaging more than one million London houses and killing more than 40,000 civilians. On the single night of 14 November 1940, Hitler sent 515 bombers against Britain in what was later called the Coventry raid. The destruction and the death toll was shocking.

Citizens had five minutes to get to shelters once the air raid sirens sounded. Many Londoners who had lost their homes to the relentless bombing simply moved into the underground subway tubes.

Courageous Londoners hunkered down every night, dusted off every morning, and picked up the pieces every day. Neighbors and families banded together. Neighborhoods organized into clearing teams. Blackout wardens comforted the living and counted the dead.

When war with Nazi Germany became imminent in the late 1930s, Great Britain began a huge effort to evacuate its children to rural areas of the country. The Ministry of Health was charged by King George VI with organizing an evacuation of as many children as possible from the urban centers to safer locales. Some children were sent to the United States, Australia, or Canada. The goal was to move them away from potential bombing targets such as London and urban centers near military production sites.

The Ministry of Health devised the Child Evacuation Scheme which was largely managed by volunteers. Although evacuation was never made mandatory, many parents put their children on the next scheduled train and sent them to parts unknown in the care of the British State simply to save them from the ravages of war.

After the first bombs fell, sending one’s children to safety was widely viewed as the responsible thing to do. Countless parents who sent their children away from the cities saved their children’s lives. At the end of the war, estimates suggest that more than 230,000 British children had been orphaned.

Every day hundreds of children wearing paper identification tags sewn to their clothing made their way, mostly by rail, to safe countryside locations. Some were fortunate enough to stay with relatives but most ended up staying with complete strangers in towns they had never before visited.

The worry and concern for their children served as a constant distraction and source of heartbreak to city dwellers who had lost nearly everything and often feared for their lives as the Nazi bombs continued to relentlessly fall overhead.

Sadly, many children were placed into group homes in the countryside or involuntarily evacuated to Australia when space got too tight to manage. Many of these children would never be reunited with their living parents at the conclusion of the war.

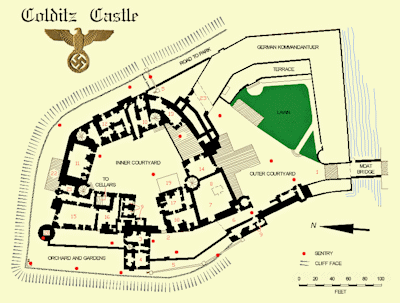

During World War II, the Germans remodeled a 400-year-old building called Colditz Castle (Schloss Colditz), a Renaissance castle located in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden, and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony in Germany. It overlooked the Mulde River and had 7-foot thick outside walls. The interior of the 6-story structure contained a maze of concealed staircases, hidden passageways, and hundreds of rooms.

Schloss Colditz aka Colditz Castle circa 1939

When they completed the work to turn the building into a prison, the Germans renamed it Oflag IV C (Sonderlager IV C) and claimed that escape would be impossible. It became the holding place for highly important prisoners and those that habitually tried to escape from other prisons.

Floor plan of Castle Colditz once converted to Oflag IV C.

On November 7, 1940, six British officers who had tried to escape from another prison camp arrived, including Rupert Barry. My towering and strong fictional character, Tom, is based on stalwart and faithful Rupert.

By Christmas, Colditz Castle held 200 prisoners – the maximum it could hold. By February 1941, another 200 French prisoners had arrived, doubling the maximum occupancy rate. By July, the Nazis held 500 POWs there.

Two of the British officers, Captain P. R. Reid and Captain Rupert Barry, worked together to create a code that Barry then wrote in a letter to his wife, Dodo, upon whom the fictional Dotty, code-named Charity, is based. The real life heroine, Dodo Barry, was a highly intelligent woman who could solve the complicated Times of London crossword puzzle in mere minutes. Captain Rupert Barry doted upon his beloved wife and, what’s more, he deeply appreciated and respected her keen mind. He felt more than confident in his wife’s abilities to crack the code they devised.

The address being written at an angle trailing up toward the stamp in the fictional story of Charity is a fiction based on numerous such factual occurrences throughout history. Soldiers during the American War Between the States would do this, hiding secret love messages beneath the postage stamps. Many spies used the same method during the First World War. During the Second World War, spies on all sides would hide microdots beneath postage stamps. The method of hiding keys and codes “under the rug” of a postage stamp became so popular, that a key to a cipher code was even hidden beneath a postage stamp in a famous Agatha Christie story.

In real life, upon receiving the letter, Dodo at first thought that conditions as a German POW had broken her dear husband’s mind. He wrote about relatives they didn’t have and referred to places they’d never visited. Then she realized that he’d written the letter in code and she spent the day deciphering the letter using nothing but her very own wits.

Decoded, it read:

Go to the War Office, ask them to send forged Swedish diplomatic papers for Reid, Howe, Allan, Lockwood, Elliott, Wardle, Milne, and self.

The next morning, Dodo went to the War Office. The officer at the desk would not let her into the building. While she stood in front of the clerk’s desk arguing with him, another officer walked by and she pleaded with him to help her. As if by providence, the officer happened to be assigned to military intelligence, a military branch with ties to MI-9.

The officer, whose name is lost to history, realized Dodo was onto something. He started working with her and had her write back to her husband and tell him, without code, that his elderly “Aunt Christine” was deeply saddened by her nephew’s capture and would write him shortly.

Under that guise, and using the same code the prisoners had created, and Dodo had deciphered, the War Office sent him a coded letter that said:

The War Office considered the use of Swedish diplomatic papers to be too dangerous.

Angry, disappointed, and frustrated with the news, instead of writing “Aunt Christine” back, Barry wrote Dodo back. Once she received his second encoded letter, she took it back to her contact at the War Office.

The deciphered message read:

We will consider the danger and not the War Office. Would you please expedite the request?

The War Office never sent the papers. However, these first “Dodo” letters had opened up a line of communication between the War Office, MI-9, and the POWs being held at Colditz Castle.

Of absolute primary importance, they needed to establish a better code.

The very tall Rupert Barry (second from the left) along with 5 former POWs pictured here outside Castle Colditz after the war.

The very tall Rupert Barry (second from the left) along with

5 former POWs pictured here outside Castle Colditz after

the war.

To anyone who spoke English, the simply encoded letters would have read as a little bit odd or disjointed. The Nazi censors often only had a rudimentary grasp of the English language, so they were able to slip by unnoticed. However, four letters in this rudimentary code was pushing their luck. Eventually, they felt the Nazis would catch on and have insight into their plans.

Under the direction of her intelligence officer, Dodo wrote a letter to Rupert explaining that an International Red Cross package would arrive with further instructions. Along with some clothing, one package contained six handkerchiefs with different colored borders. Coded instructions in Dodo’s letter directed Barry to place the green bordered handkerchief in hot water and stir for several minutes. Soon, a more elaborate code appeared in hidden ink on the handkerchief. Barry memorized the code then destroyed the material. Over time, she shared the code with his fellow prisoners who also memorized it.

With well coded letters and hidden supplies contained in Red Cross packages, the MI-9 office (escape and evasion service) supplied the prisoners in Colditz with money, identification documents, radios, tools, train schedules, border crossing policies and routines, clothing, and even weapons.

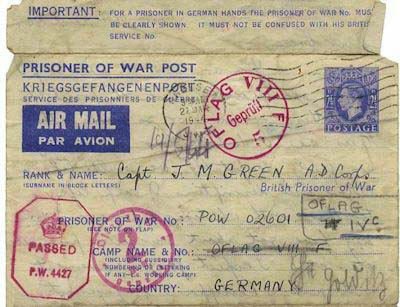

Letter from Colditz sent home to Scotland by POW Captain

Julius Morris Green. A dentist before the war, Green was

captured fighting the Nazis at Dunkirk in 1940. Green sent

more than 40 coded letters home once the letters sent to

Dodo bore fruit.

The war effort was greatly aided by critical intelligence sent home from the prisoners. One such prisoner, a skilled dentist, was often called upon to treat German soldiers and officers as well as his fellow prisoners. He sent letters back home to Scotland and the ones that began “Dear Dad” often contained crucial information pertaining to troop movements inside Germany.

With the aid of the secreted supplies and intelligence MI-9 could provide via this now secure communication channel, 130 prisoners escaped from Colditz Castle – either successfully or unsuccessfully – over a 5 year period.

Of those 130 escaped prisoners, 32 of them escaped successfully. In all, 12 Frenchmen, 11 Britons, 7 Dutch, and 1 Polish prisoner of war made it all the way home, a feat that came to be known as a Home Run. This number of prisoners of war escaping and making it all the way back home is unequaled in modern warfare. Among these successful escapees was Captain P. R. Reid who had helped Rupert Barry pen that very first letter to his wife, Dodo.

Because of Dodo, also the name of a now extinct bird, the Colditz Castle escapees came to be known as the “Birdmen of Colditz” and their escapes and attempted escapes have been the subject of many books, films, and even a BBC television series. Very few photographs of Dodo or her husband survive today.

Selected for the cover of this book is the incredible Yolande Betbeze (ne Fox) who may be most well known for her association with baseball great Joe Dimaggio, her marriage to movie tycoon Matthew Fox until his death, her activism in the 1960s, and for taking the Miss America crown in 1950. While not exactly a British housewife with “island blood,” the publisher felt that this woman’s indomitable spirit strongly represented the fictional character of Charity.

Selected for the cover of this book is the incredible Yolande Betbeze (ne Fox) who may be most well known for her association with baseball great Joe Dimaggio, her marriage to movie tycoon Matthew Fox until his death, her activism in the 1960s, and for taking the Miss America crown in 1950. While not exactly a British housewife with “island blood,” the publisher felt that this woman’s indomitable spirit strongly represented the fictional character of Charity.

Excerpt from her official Miss America bio: “Always courageous and sometimes controversial, Yolande has always been ahead of her time, tackling tough issues and making a stand before the issues at hand were fashionable.”

Born in 1929 to William and Ethel of Mobile, Alabama, Yolande was raised in a strict Catholic family with Basque origins and was educated in a convent school. In 1950 shortly after her twentieth birthday, Betbeze traveled to Atlantic City, New Jersey, to compete in the Miss America pageant. Beyond her beauty and her operatic musical talent, Yolande handily took top honors for her scholarship, values, and leadership.

After winning the competition, she made no secret of her reluctance to don what she considered a very immodest swimsuit (tame by modern standards) and her refusal caused Catalina swimwear to withdraw their sponsorship from the pageant. To this day, the Miss America Organization claims that her actions were pivotal in directing the Miss America Pageant toward recognizing intellect, values, and leadership abilities, rather than focusing on beauty alone. From then on the Miss America pageant concentrated more on scholarship than beauty. Since there was no Miss America in 1950, Betbeze became the reigning Miss America in 1951.

After her year as Miss America, Yolande served as an ambassador to postwar Paris, France and was active in both the NAACP and CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) upon her return to the United States. She never lost her love for opera, even appearing with the Mobile Opera Guild (the Mobile Opera today), and helped found an off-Broadway theater.

Read about Dorothy Ewing, code-named CHARITY, who was inspired by the amazing Dodo Barry, in Charity’s Code, FREE November 3-7 at this link.